Black and white photography -- developing images

Once, there is a latent image in a sheet of paper, with partially exposed silver halide emulsion, then the image needs to be made visible.

In a modern emulsion, the crystals of AgX are very small. These crystals are called 'grains' in photography. Typical grain size is in the order of magnitude of several micrometers, even down to hundreds of nanometers. Despite its small size, a grain still consists of billions of AgX units and hence still contains billions of silver ions.

During the development process, grains of AgX are reduced to grains of metallic silver, and the halide is released as free ion and goes in the developer solution.

The entire idea behind silver-based photographic processes, is that grains, which contain free metallic silver atoms, which were produced by exposure to light (latent image, see previous page) are reduced much more easily than grains without free metallic silver atoms.

Development of latent image to visible image

The sheet with the latent image is immersed in a so-called developer solution, which is a solution of chemicals, such that it has mild reducing properties. The grains with free metallic silver atoms are reduced to metallic silver completely within a few minutes, while other grains, which have no free metallic silver atoms in them hardly are affected in this time. So, effectively, developing a latent image to a visible image, is nothing more than immersing the sheet in a developer solution for such a long time that the latent image is completely converted to metallic silver, while at the same time, the non-exposed parts of the sheet still are not reduced at all. With modern emulsions, this is not a problem at all. For suitably chosen reductors, the rate of reduction of exposed grains is thousands or even millions times larger than the rate of reduction of non-exposed grains.

Choice of reducing agent for development

The reductor, used for developing an exposed image, must be strong enough to quickly reduce exposed grains, while at the same time, non-exposed grains are not affected, or only very slowly. Many reductors are too strong and they also reduce non-exposed grains. If this occurs, then the entire sheet becomes black. If this occurs partially, then the latent image still becomes visible, but the non-exposed areas become grey. This effect is known as fogging. A careful choice of reductor(s) and careful adjustment of the conditions, in which the reductors are used, allows good developing with complete reduction of the latent image, while no fogging occurs.

In the past, many different reductors have been tried, and also combinations of reductors have been tried. Frequently this work was simply trial and error, because no theoretical basis existed for their choice. Despite this trial and error method, very good developers and also very good emulsions were available already before world war II, while there was no theoretical foundation at that time at all.

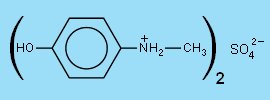

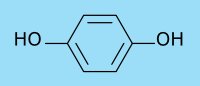

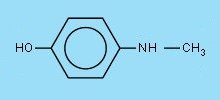

Modern developers are based on derivatives of phenol, which are easily oxidized. These are the ortho- and para-derivatives of phenol (polyphenols, or phenols with added -NH2 groups). During the years a few compounds appeared outstanding, both in developing properties, and in storage properties. These are p-(methylamino)phenol, or salts derived from this, and p-dihydroxybenzene. Nowadays, by far the largest amount of developers used for virtually all kinds of black and white photography are based on the two compounds, mentioned above. The sulfate salt of p-(methylamino)phenol is used, because it stores better than the free base, but in the developer solution, the free base is present. The common names of these chemicals are metol and hydroquinone. The chemical structure of these two compounds is shown below.

In the alkaline developer solutions, the metol sulfate salt dissolves and is deprotonated. The free base p-(methylamino)phenol is the active species in solution.

Conditions of development, basics of developer solutions

An exposed sheet, with a gelatin-based silver halide emulsion, simply is immersed in the developer solution. With only hydroquinone or metol in solution, the process is very slow. These developers work best in alkaline conditions. The more alkaline the solution, the stronger its reducing properties. A good developer solution has a pH around 11. Some fast acting developers may go as high as 13. A big disadvantage of high pH, in combination with phenol-derivatives is that such solutions have very bad storage properties. The solutions absorb oxygen from the air and the solutions become useless within minutes, when exposed to air with large surface area (which is typically the case in normal developing trays for large size images). In order to make the alkaline developer solutions less prone to aerial oxidation, sodium sulfite is added to the solutions. The sulfite provides some alkalinity, and besides that, it protects towards aerial oxidation. So, a basic developer already can be made as follows:

- hydroquinone or metol (acting as reductor);

- sodium sulfite (for high pH and for protection against aerial oxidation).

In the developer solutions at high pH, the reaction occurs through the intermediate formation of so-called semiquinone radicals. The higher the pH, the easier the formation of the semiquinone radicals. For hydroquinone, this reaction looks as follows:

HOC6H4OH + AgX → HOC6H4O· + [H>·AgX]

[H>·AgX] + OH– → Ag + X– + H2O

Here [H>·AgX] is not a real chemical species, this notation stands for the process of transfer of a hydrogen atom to the AgX lattice, where an electron is transferred from the hydrogen atom to a silver ion in (very near the surface of) the lattice, resulting in formation of metallic silver and release of the halogenide ion X–. At the same time, the hydrogen atom looses an electron and this at once reacts with hydroxide to form water. If no hydroxide ion is present, then the hydrogen atom does not loose its electron, and hence no development process occurs. The presence of hydroxide ion is very important.

The semiquinone radicals in turn react with each other, or with other compounds in the solution, giving rise to many different (often polymeric) species, which appear as dark brown material. A spent developer solution has a brown color, a fresh developer solution is colorless.

Superadditive effect, dramatic improvement of developer properties

With hydroquinone alone, or with metol alone, the developer solution still is not working optimally. Hydroquinone has a fairly high reduction potential, but it has difficulty adhering to the surface of the silver halide grains. This limits its effectiveness as reductor in the developer solution. Metol on the other hand, adheres to the silver grains quite well (in alkaline solutions, its N-atom has a free electron pair, which nicely coordinates to silver ions), but it has lower reduction potential. It has difficulty transferring an electron to the silver ion. When both metol and hydroquinone are present in solution, then a new effect occurs, which makes the solution much more effective in reducing the silver halide grains to metallic silver. A solution, containing both reductors shows a much higher rate of reduction than the sum of the rates of reduction of both reductors used alone.

The mechanism behind this superadditive effect is that each of the reductors has its own role in the solution. Metol adheres to the silver halide grains. When a molecule of hydroquinone comes nearby, then the metol acts as an electron transfer agent. The metol reduces the silver halide, but at the same time, the hydroquinone reduces the metol. The net effect is that the metol remains unchanged, it only works as a 'tunnel' for the electron, moving from the hydroquinone to a silver ion in the silver halide lattice. The metol actually can be regarded as a catalyst. The hydroquinone looses an electron and it forms the semiquinone radical HOC6H4O· and it splits of H+, which at once reacts with OH– in the alkaline solution.

So, a much better developer consists of a solution of

- metol

- hydroquinone

- sodium sulfite (for high pH and protection against aerial oxidation)

- optionally some extra sodium carbonate can be added for additional mild alkalinity if the developing solution works too slow

In practice, this simple developer already is used quite a lot. However, for an allround developer solution which can be used in a wide range of applications, one more component must be added.

Anti fogging, restraining

If a developer, based on metol, hydroquinone and sodium sulfite is used, then it might happen that, despite the large difference in the rate of reduction of exposed parts and unexposed parts, some of the unexposed parts of the image obtain a faint grey color. Even a 1 : 1000 reduction of silver halide grains already gives a visible grey color. This effect is called fogging and it is highly undesirable if one wants a brilliant fresh-looking print.

The action of the anti-fogging agents is based on their property to decrease the solubility of silver halide in solution. If AgX were completely insoluble, then the development process would be extremely slow, because it would be a 100% interface process, possible only at the interface between the solid grains and the liquid developer. In reality, AgX is slightly soluble and near the surface of the grains, there is an equilibrium:

AgX(s) ↔ Ag+(aq) + X–(aq)

The developer acts on Ag+ very close to the surface of the grains, where the ions are less tighly fit into the crystal lattice. At places with a latent image, which already has been partially reduced to a visible image, quite some silver halide is converted to silver metal, and at those places, free halide ions go into solution. Due to these free halide ions, the solubility of the silver halogenide is reduced and the process of development goes slower than in the initial stage of development. At places, where there is no developed latent image, the halide concentration still is low, and at those places, the inhibiting action of the halide ions is not present. So, in a developing solution, the rate of reduction remains constant in unexposed areas, while it slowly decreases at exposed areas.

What is done in practice is the addition of a small amount of potassium bromide to the developer solution. This has the effect, that the halide concentration in the developer solution is practically the same at every place, regardless of whether it is in the partially reduced latent image areas or in the unexposed areas. This is true as long as the concentration of the added halide ions is much higher than the concentration of the halide ions, coming from the grains.

The net effect of adding the potassium bromide is that the developer acts more slowly overall, but the ratio of rate of reaction in latent image areas to the rate of reaction in unexposed areas becomes larger. For the photographer, this is visible as slower action, but better contrast. The photographer can keep the print in the developer for a longer time, such that the exposed areas can become deep black, while the unexposed areas remain white for a longer time.

So, a really allround developer contains the following ingredients:

- metol

- hydroquinone

- potassium bromide (for reduction, also called restrainer)

- sodium sulfite (for high pH and protection against aerial oxidation)

- optionally some extra sodium carbonate can be added for additional mild alkalinity if the developing solution works too slow

Normally, potassium bromide (or sodium bromide) is used as restrainer. AgBr is much less soluble than AgCl, so it works already at low concentration. Potassium iodide (or sodium iodide) is not used as restrainer. The solubility of AgI is so low, that this would make the developing action too slow.

Since a few decades, more advanced restrainers are available. These have the same effect as the addition of potassium bromide (increasing the ratio of reduction rate at latent image to the rate of reduction rate at unexposed areas), but without the negative effect of slower development. These restrainers usually need to be added at very low concentrations of just a few mg per liter of working solution.

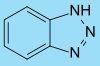

One such an anti fogging agent is benzotriazole:

A good general allround developer is the following, which can be used for film negatives and for prints: http://www.jackspcs.com/gaf125.htm.

Stopping the development process

Once a print is completely developed, i.e. the exposed areas have reached the desired level of blackness, then the development process must be stopped as quickly as possible. Otherwise, the reduction of silver halide to silver metal will continue and finally the print will become completely black. This stopping of the development process is covered in the next webpage.