Cationic species of Te, Se and S

Tellurium, selenium and sulphur are capable of forming cationic species, consisting of the elements only. The chemistry of these species is relatively unknown. More common are the anionic species, such as sulfide, selenide and telluride and the polyanions, like polysulfide. Also much better known are the oxo-anions of these elements, such as sulfate, sulfite, selenate, tellurate.

In this experiment cationic species of tellurium, selenium and sulphur are made. With tellurium, this can be done fairly easily with concentrated sulphuric acid, with selenium it is more difficult, but still possible, but for sulphur, no cationic species could be prepared without the use of oleum. With the use of 20% oleum, however, also the sulphur species could be prepared without difficulty.

The following ions are reported in literature:

- deep red/purple Te42+

- yellow Se42+

- deep green Se82+

- yellow S42+

- deep blue S82+

- deep red S192+.

Which ion is formed for a given element depends on the experimental conditions (type of solvent, temperature, used oxidizer).

All these ions are extremely water-sensitive and the presence of water is an absolute no-go when one wants to prepare these ions. An oxidizer is needed under anhydrous conditions, with a solvent, capable of dissolving ionic species. One such solvent is concentrated sulphuric acid, with the optional addition of some phosphorus pentoxide in order to get really rid of water. In the case of sulphuric acid, no oxidizer needs to be added, sulphuric acid can act both as the solvent and as the oxidizer.

Three experiments are described below, one for tellurium, one for selenium and one for sulphur.

In

this experiment, very hot concentrated sulphuric acid (300 ºC or so) is

prepared. This is an EXTREMELY corrosive liquid and utmost care should be

exercised when doing this experiment. Any spill must be avoided. It will

burn holes instantly in wood, paper, fabric, and also skin. Use

glassware, which you really trust. A cracking test tube can have nasty

consequences. Wounds resulting from contact with this liquid will be severe and deep. Be warned, when doing this

experiment. The experiment with sulphur requires heating of oleum, which is even

more corrosive than sulphuric acid alone!

In

this experiment, very hot concentrated sulphuric acid (300 ºC or so) is

prepared. This is an EXTREMELY corrosive liquid and utmost care should be

exercised when doing this experiment. Any spill must be avoided. It will

burn holes instantly in wood, paper, fabric, and also skin. Use

glassware, which you really trust. A cracking test tube can have nasty

consequences. Wounds resulting from contact with this liquid will be severe and deep. Be warned, when doing this

experiment. The experiment with sulphur requires heating of oleum, which is even

more corrosive than sulphuric acid alone!

![]()

![]() Required

chemicals:

Required

chemicals:

-

sulphuric acid, concentrated acid, 96%

-

tellurium

-

selenium

-

sulphur

-

potassium dichromate

-

sodium hypophosphite (or any other decent reductor)

-

sodium sulfide

-

hydrogen peroxide, 3%

-

phosphorus pentoxide (optional, when the acid is less concentrated)

-

oleum (sulphuric acid with 20% SO3 dissolved in it)

![]() Required

equipment:

Required

equipment:

-

small oil burner or alcohol burner

-

test tube, which really can be trusted at 300 ºC or even somewhat more

-

small beaker or erlenmeyer

![]() Safety:

Safety:

-

Take utmost care when handling the very hot acid.

Take utmost care when handling the very hot acid. -

Avoid exposure to

any fumes in the tellurium experiment. Tellurium is not extremely toxic, but

even inhalation of tiny amounts of tellurium compounds may lead to very bad

body smell for weeks or even months. There are reports of people, stinking

for weeks after exposure to only a few hundreds of micrograms of tellurium.

Avoid exposure to

any fumes in the tellurium experiment. Tellurium is not extremely toxic, but

even inhalation of tiny amounts of tellurium compounds may lead to very bad

body smell for weeks or even months. There are reports of people, stinking

for weeks after exposure to only a few hundreds of micrograms of tellurium. -

Selenium is very toxic, but the amount, used in this experiment is so small, that harmful exposure to this is unlikely.

-

Some sulphur dioxide is produced in the experiment with tellurium. This is very pungent. But in this experiment, actually, it is good that sulphur dioxide is produced. If you smell any sulphur dioxide during the tellurium experiment, then immediately leave the room. In that case, there also can be volatile tellurium compounds in the air, but when you just smell the sulphur dioxide, then it is unlikely that you already have inhaled so much tellurium that you will be stinking for a long time. Fortunately, the tellurium compounds, formed in this experiment are non-volatile.

-

Potassium dichromate contains hexavalent chromium. This most likely is a carcinogen, so avoid exposure to this chemical.

-

Sodium sulfide forms hydrogen sulfide when added to acid. The latter has a bad smell and is very toxic. It numbs your sense of smell and as such, it looses its warning properties. The experiment, however, only calls for 50 to 100 mg of this chemical, and if you stick to such small quantities, then no serious risk exists, other than getting a stinky room.

![]() Disposal:

Disposal:

-

The only chemicals, used in appreciable amount, are sulphuric acid and hydrogen peroxide. The other chemicals only are used in milligram quantities and hence the waste can be flushed down the drain with a lot of water.

![]()

Tellurium in sulphuric acid at moderate heat

![]() Take a small piece of tellurium. A piece of 30 mg or so is

more than sufficient. The pictures below show the piece of tellurium, a close-up

and the piece in a standard size test tube.

Take a small piece of tellurium. A piece of 30 mg or so is

more than sufficient. The pictures below show the piece of tellurium, a close-up

and the piece in a standard size test tube.

The piece of tellurium has a thickness varying between 0.5 mm and 1 mm and a diameter of approximately 2.5 mm.

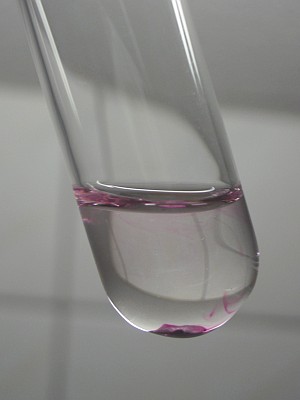

![]() To this

piece of tellurium add 1.5 to 2 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid and then heat

the test tube slowly above a small flame. Soon, pink 'waves' emerge from

the piece of tellurium, and it definitely is not necessary to strongly heat the

acid. With tellurium, the reaction is easily performed. The four pictures below

show the tellurium in cold acid and what happens when it is heated and swirled

slowly.

To this

piece of tellurium add 1.5 to 2 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid and then heat

the test tube slowly above a small flame. Soon, pink 'waves' emerge from

the piece of tellurium, and it definitely is not necessary to strongly heat the

acid. With tellurium, the reaction is easily performed. The four pictures below

show the tellurium in cold acid and what happens when it is heated and swirled

slowly.

![]() Continue

heating for a while, and occasionally swirl the test tube and let it cool down

for a few seconds. In this way, the acid becomes quite hot, but certainly it

will not go near its boiling point. The liquid becomes darker and darker, and at

a certain point it becomes very deep purple/red.

Continue

heating for a while, and occasionally swirl the test tube and let it cool down

for a few seconds. In this way, the acid becomes quite hot, but certainly it

will not go near its boiling point. The liquid becomes darker and darker, and at

a certain point it becomes very deep purple/red.

![]() An

interesting effect is obtained, when the hot purple solution is poured in water.

This must be done very carefully

and one must use a large excess amount of water.

When the hot liquid touches the surface of the water, then there is a loud

crackling noise, which is rather scary!

An

interesting effect is obtained, when the hot purple solution is poured in water.

This must be done very carefully

and one must use a large excess amount of water.

When the hot liquid touches the surface of the water, then there is a loud

crackling noise, which is rather scary! ![]() Failing to use a large excess amount of water most likely will result in

severe injury, due to the extremely violent reaction and the risk of hot acid

droplets sprayed around.

Failing to use a large excess amount of water most likely will result in

severe injury, due to the extremely violent reaction and the risk of hot acid

droplets sprayed around.

A black finely divided precipitate is formed, when the red/purple liquid is added to water. These black particles consist of elementary tellurium. The picture below shows the result of adding a small part of the purple/red liquid to a large excess of water. Only the lower part of the liquid contains the black precipitate. This is due to the higher density of the acid/water mix, which is formed on contact of the red/purple liquid with water.

![]() The

remaining part of the liquid becomes darker and darker, while more tellurium

dissolves in the concentrated acid. First, a picture is made directly after

adding a few drops to water, and then another picture is made, a few minutes

later, while keeping the liquid hot. The picture was made with strong light

going through the liquid, otherwise it simply would look black.

The

remaining part of the liquid becomes darker and darker, while more tellurium

dissolves in the concentrated acid. First, a picture is made directly after

adding a few drops to water, and then another picture is made, a few minutes

later, while keeping the liquid hot. The picture was made with strong light

going through the liquid, otherwise it simply would look black.

![]()

Tellurium in sulphuric acid at strong heat

Now, the experiment is continued with much stronger heating, such that the acid goes near boiling. White fumes are emitted from the acid (it partly decomposes, giving sulphur trioxide and water) and it becomes very hot. This stage of the experiment is even more hazardous than the experiment above, due to the very hot concentrated acid.

![]() At a certain point in time, the liquid starts bubbling fairly

vigorously and at this point, the white fumes also become more and more dense.

At the same time, the liquid becomes turbid and some white crystalline solid is

formed. The left picture shows the bubbling of the liquid and the formation of a

solid. Both pictures nicely show the thick fumes above the liquid. The right

picture shows a

white precipitate below the purple liquid.

At a certain point in time, the liquid starts bubbling fairly

vigorously and at this point, the white fumes also become more and more dense.

At the same time, the liquid becomes turbid and some white crystalline solid is

formed. The left picture shows the bubbling of the liquid and the formation of a

solid. Both pictures nicely show the thick fumes above the liquid. The right

picture shows a

white precipitate below the purple liquid.

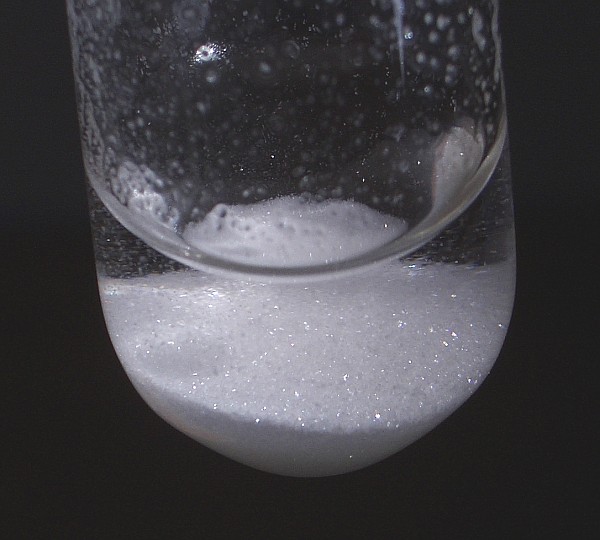

![]() When heating at near boiling of the acid is continued, then

the purple color slowly fades and after two minutes or so, the purple color has

disappeared completely, and a crystalline precipitate can be observed at the

bottom. The picture below shows the test tube with the acid still very hot (well

above 200 ºC). No trace of a purple compound can be observed anymore.

When heating at near boiling of the acid is continued, then

the purple color slowly fades and after two minutes or so, the purple color has

disappeared completely, and a crystalline precipitate can be observed at the

bottom. The picture below shows the test tube with the acid still very hot (well

above 200 ºC). No trace of a purple compound can be observed anymore.

When this liquid is allowed to cool down, then the crystals grow somewhat larger and nice glittering crystals can be observed. Below is a picture of the crystals, with a dark background and sunlight shining on them.

There is a lot of a crystalline precipitate under the concentrated sulphuric acid.

It is remarkable to see such a voluminous precipitate, when it is compared to the small size of the piece of tellurium used at the start of the experiment.

![]()

Formation of an aqueous solution with tellurium(IV)

When a lot of water is added at once to the cooled down (!!!) acid with the white solid, then the white solid quickly dissolves with a little shaking and a colorless liquid is obtained. This liquid can be easily reduced, but it also can be easily oxidized. When part of this liquid is added to a solution of sodium hypophosphite (but also to other strong reductors, like dimethylamine borane complex, or sodium borohydride), then immediately a black precipitate is formed. This black precipitate is elementary tellurium. On the other hand, when potassium dichromate is added to the colorless liquid, then the dichromate quickly is reduced to green/blue chromium(III). The colorless liquid contains tellurium in the +4 oxidation state as acidified TeO2. This can be reduced to Te, and it can be oxidized to tellurate, with tellurium in the +6 oxidation state.

The following three pictures show the colorless solution, which is the result of adding a lot of water to the acid with the white crystalline solid. The middle picture shows the result of adding some of the colorless liquid to a solution of sodium hypophosphite, and the right picture shows the result of adding some solid potassium dichromate to a small amount of the colorless liquid.

When some hydrogen peroxide is added to the test tube with the black precipitate, then the precipitate quickly dissolves, giving a colorless solution again. Hence, finely divided elementary tellurium easily is oxidized by hydrogen peroxide in acidic medium.

![]() Finally, to some of the colorless liquid, a solution of

sodium sulfide is added (50 to 100 mg of sodium sulfide in 2 ml of water). This results in formation of a dark brown precipitate.

The large picture below shows the result of adding just a single drop of a

solution of sodium sulfide. The smaller picture at the left shows the result of

adding much more solution of sodium sulfide. It shows that a dark brown liquid

is formed, with a thick and coarse precipitate, which quickly sinks to the

bottom. Again, this precipitate dissolves in excess hydrogen peroxide, but not

as easily as elementary tellurium. The right picture shows the result after

adding hydrogen peroxide and shaking. The liquid becomes clear and colorless

quickly, but the larger particles take a longer time to dissolve.

Finally, to some of the colorless liquid, a solution of

sodium sulfide is added (50 to 100 mg of sodium sulfide in 2 ml of water). This results in formation of a dark brown precipitate.

The large picture below shows the result of adding just a single drop of a

solution of sodium sulfide. The smaller picture at the left shows the result of

adding much more solution of sodium sulfide. It shows that a dark brown liquid

is formed, with a thick and coarse precipitate, which quickly sinks to the

bottom. Again, this precipitate dissolves in excess hydrogen peroxide, but not

as easily as elementary tellurium. The right picture shows the result after

adding hydrogen peroxide and shaking. The liquid becomes clear and colorless

quickly, but the larger particles take a longer time to dissolve.

It seems that this is a different compound. Its color also is different. It is not purely black, but dark brown. Its color is nicely demonstrated by this picture:

![]()

Selenium in hot sulphuric acid

![]() Take a small piece of selenium. A piece of 20 mg or so is

more than sufficient. The pictures below show the piece of selenium: a close-up

and the piece in a standard size test tube (16 mm x 16 cm).

Take a small piece of selenium. A piece of 20 mg or so is

more than sufficient. The pictures below show the piece of selenium: a close-up

and the piece in a standard size test tube (16 mm x 16 cm).

The piece of selenium has a thickness of approximately 1 mm and a diameter of approximately 2 mm.

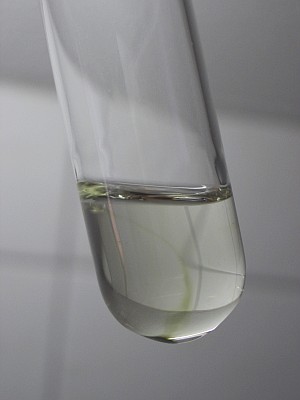

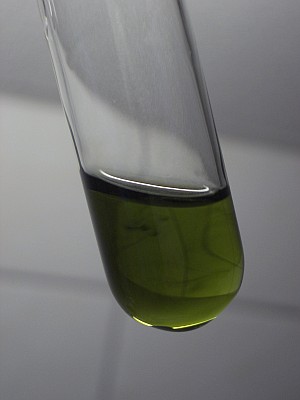

![]() To this

piece of selenium add 1.5 to 2 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid and then heat

the test tube slowly above a small flame. Quite some heat must be

applied, before any reaction can be observed. Compared with the experiment with

tellurium, getting the selenium to react with the concentrated acid is much

harder. Tellurium already dissolves when only moderate heat is applied, for

selenium, one must go to the point, where the acid is close to producing white

fumes. This is well beyond 200 ºC, and probably even close to 300 ºC. But

finally, when the acid is really hot, green 'waves' emerge from the piece of

selenium. The six pictures below show the selenium in cold acid and what happens when it is

strongly heated and swirled

slowly.

To this

piece of selenium add 1.5 to 2 ml of concentrated sulphuric acid and then heat

the test tube slowly above a small flame. Quite some heat must be

applied, before any reaction can be observed. Compared with the experiment with

tellurium, getting the selenium to react with the concentrated acid is much

harder. Tellurium already dissolves when only moderate heat is applied, for

selenium, one must go to the point, where the acid is close to producing white

fumes. This is well beyond 200 ºC, and probably even close to 300 ºC. But

finally, when the acid is really hot, green 'waves' emerge from the piece of

selenium. The six pictures below show the selenium in cold acid and what happens when it is

strongly heated and swirled

slowly.

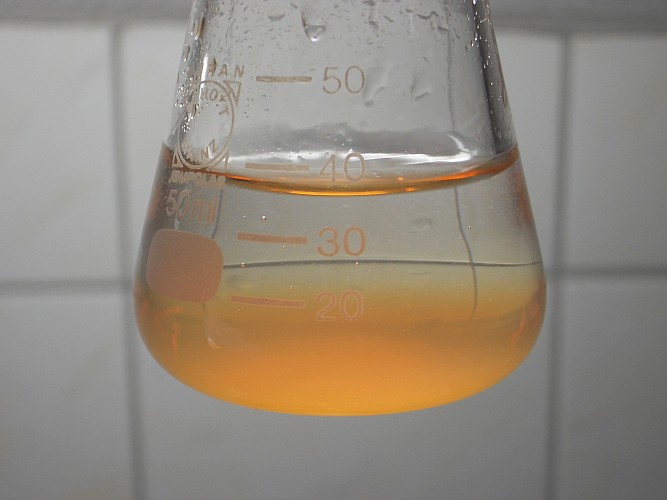

![]() When a

few drops of the very hot acidic green liquid are added to a large excess amount

of water, then a beautiful orange/red precipitate is formed. This is the red

allotrope of selenium, very finely divided in the liquid. This part of the

experiment requires extreme caution, even more so than with the experiment with

tellurium. Concentrated sulphuric acid of more than 200 ºC reacts explosively

violently with water. Use a really large excess amount of cold water and a flask with a

narrow neck and drip in the acid. Use good protection for hands and arms while

doing this. The result of this operation is shown in the picture below:

When a

few drops of the very hot acidic green liquid are added to a large excess amount

of water, then a beautiful orange/red precipitate is formed. This is the red

allotrope of selenium, very finely divided in the liquid. This part of the

experiment requires extreme caution, even more so than with the experiment with

tellurium. Concentrated sulphuric acid of more than 200 ºC reacts explosively

violently with water. Use a really large excess amount of cold water and a flask with a

narrow neck and drip in the acid. Use good protection for hands and arms while

doing this. The result of this operation is shown in the picture below:

Again, only the lower part of the liquid has the finely divided element, because of the higher density of the acid/water mix, which is formed when the acid is dripped into the water.

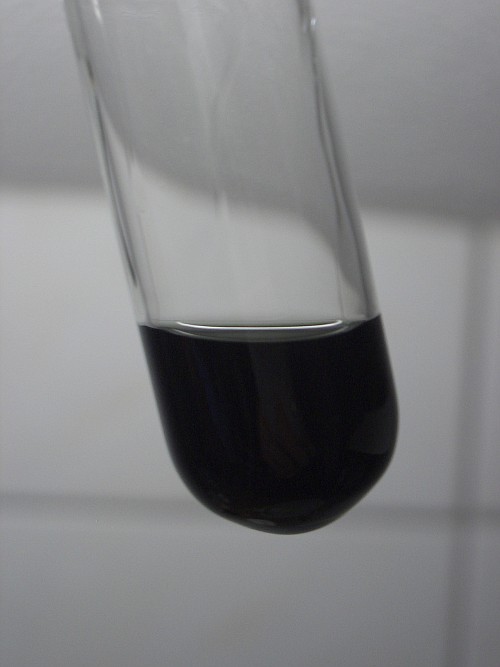

![]() After a

few drops of green liquid are dripped in water, the test tube is heated even

more strongly for a longer time. This results in dissolving of all selenium, and

the liquid becomes really dark, almost black. Prolonged heating does not result

in disappearing of the deep green color. This is a difference with the

experiment with tellurium. The picture below shows the almost black liquid,

which already has cooled down a little bit (but still is estimated to be around

200 ºC).

After a

few drops of green liquid are dripped in water, the test tube is heated even

more strongly for a longer time. This results in dissolving of all selenium, and

the liquid becomes really dark, almost black. Prolonged heating does not result

in disappearing of the deep green color. This is a difference with the

experiment with tellurium. The picture below shows the almost black liquid,

which already has cooled down a little bit (but still is estimated to be around

200 ºC).

When this dark liquid is swirled around a bit, then the liquid, which is running along the glass downwards is dark green, but it quickly changes color to red and becomes turbid. The green cationic species easily is converted (at least partially) to elementary selenium. Most likely this is due to absorption of water from the air (the experiment was done on a warm and humid day).

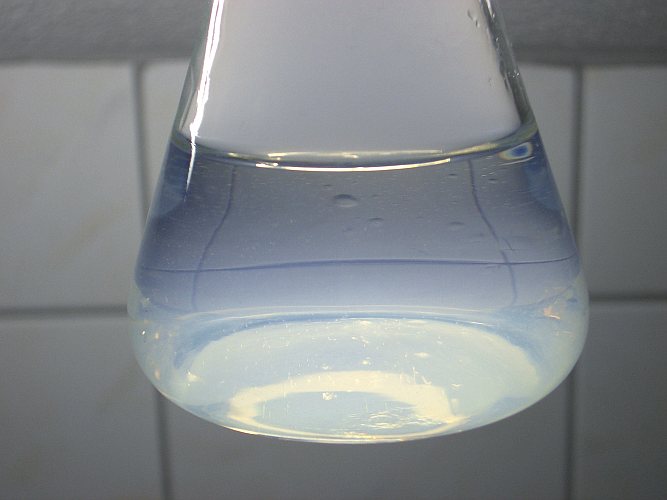

![]() Finally,

the dark liquid was allowed to cool down somewhat and then all of the liquid

carefully was added to a large excess of cold water. This results in a

violent reaction between the acid and the water and immediate formation of a

large amount of bright brick-red precipitate.

Finally,

the dark liquid was allowed to cool down somewhat and then all of the liquid

carefully was added to a large excess of cold water. This results in a

violent reaction between the acid and the water and immediate formation of a

large amount of bright brick-red precipitate.

Initially, this precipitate is very finely divided, but the small particles quickly stick together and a clumpy and very voluminous piece of precipitated selenium is formed at the bottom. After an even longer time, the piece of precipitate moves upwards to the surface, most likely due to formation of small bubbles of air, which stick to the piece of precipitate and take this upwards. By swirling around the liquid in the erlenmeyer, the piece of precipitate can easily be made to sink to the bottom again.

![]()

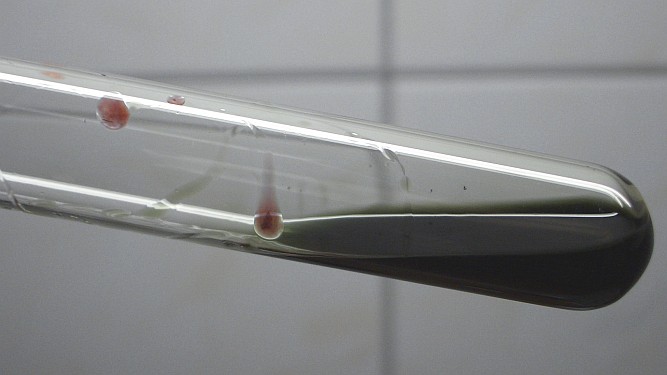

Sulphur in hot sulphuric acid (with P4O10 added)

With tellurium, it was fairly easy to prepare the red/purple cationic species in sulphuric acid. With selenium, it was harder already and strong heating was needed. When a similar experiment is done with sulphur in concentrated sulphuric acid, then no colored species are formed at all and the sulphur does not dissolve.

Finally, the experiment with sulphur was repeated with phosphorus pentoxide added to the concentrated sulphuric acid, in order to take away all traces of water and to make even some sulphur trioxide (quite some P4O10 was added). Even with this liquid and strong heating no sulphur can be dissolved.

What was observed though was that the sulphur first melts, giving nice yellow droplets in the liquid.

When the liquid is heated further, then the droplets darken, as the sulphur polymerizes and on even stronger heating, the droplets of sulphur become deep red and more mobile. They easier combine into a bigger droplet at the higher temperature. The picture below shows two larger blobs of very hot molten sulphur, together with some smaller droplets.

The liquid is somewhat brown in this experiment, this is not due to dissolving of sulphur into the acid, but due to an impurity in the phosphorus pentoxide used. Although this is a perfectly white powder, on dissolving this in water, or sulphuric acid, it forms a pale brownish liquid, when at higher concentration.

A nice and funny end was given to this experiment, by allowing the liquid to cool down. During the cooling down, the color of the sulphur reverts to yellow, and at the point, where the sulphur formed a few yellow droplets, the liquid at once was poured into a bucket filled with cold water. This gives a loud and scary crackling noise and results in little splashes sprayed around (the acid still was quite hot, and the phosphorus pentoxide makes it even more eager for reacting with water). In the cold water the droplets of sulphur solidify and sink to the bottom. They were collected, rinsed, and dried with a paper tissue. The result is shown in the picture below. The largest sphere has a diameter of approximately 2 mm.

![]()

Sulphur in hot oleum with 20% SO3

As the experiment above demonstrates, sulphuric acid is not capable of producing any cationic species of sulphur. With oleum, containing 20% dissolved SO3, the reaction is easily carried out though.

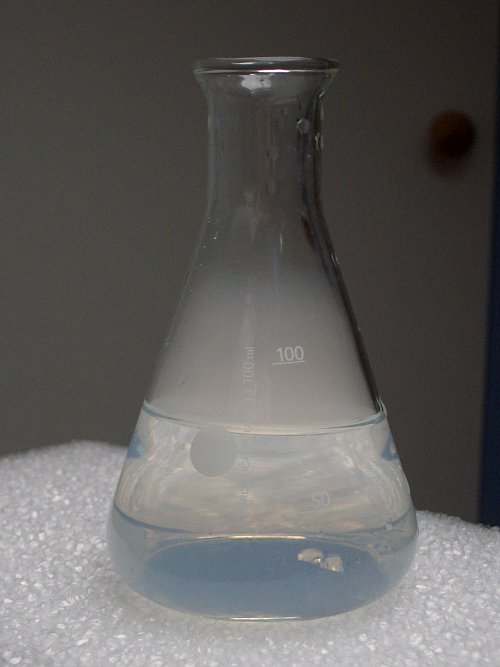

When some sulphur is added to the oleum, then at room temperature, already a faint blue color can be observed. Moderate heating quickly dissolves all of the sulphur and an extremely intensely blue color is obtained.

![]() In this experiment, 10 to 20 mg of sulphur is put in an

absolutely dry test tube, and then approximately 1 ml of 20% oleum is added.

When the test tube is heated then the sulphur quickly dissolves, only moderate

heating is required.

In this experiment, 10 to 20 mg of sulphur is put in an

absolutely dry test tube, and then approximately 1 ml of 20% oleum is added.

When the test tube is heated then the sulphur quickly dissolves, only moderate

heating is required.

When only a small part of the sulphur has dissolved, then the liquid already has a very deep blue color. When all sulphur has dissolved, then the liquid is almost black. The left picture below shows the liquid when only some sulphur has dissolved, the right picture shows the liquid when all sulphur has dissolved.

![]() When the liquid is allowed to cool down and poured in a large

excess amount of cold water, then a finely divided precipitate of elemental

sulphur is produced. The liquid has the smell of sulphur dioxide, but also some

hydrogen sulfide can be observed. This experiment is hazardous. The reaction

between oleum and water is extremely violent, a loud roaring noise is produced

when the oleum is poured in the water.

When the liquid is allowed to cool down and poured in a large

excess amount of cold water, then a finely divided precipitate of elemental

sulphur is produced. The liquid has the smell of sulphur dioxide, but also some

hydrogen sulfide can be observed. This experiment is hazardous. The reaction

between oleum and water is extremely violent, a loud roaring noise is produced

when the oleum is poured in the water.

The sulphur is so finely divided, that the color of the light from above seems blue, due to Rayleigh scattering. Above the liquid, there is a thick white fume of sulphur trioxide, release from the oleum when it was poured in the water. Even after a few minutes, the fume still is clearly visible and the liquid looks blue at the bottom of the erlenmeyer, still due to the scattering of the light.

![]()

Discussion of results

![]() Tellurium reacts with sulphuric acid at elevated temperature

as follows:

Tellurium reacts with sulphuric acid at elevated temperature

as follows:

4Te + 3H2SO4 → Te42+ + SO2 + 2H2O + 2HSO4–

The sulphuric acid oxidizes the tellurium, but only mildly. The acid itself is reduced to sulphur dioxide (which actually could be smelled faintly during the experiment). Any water, formed in the reaction, is captured by the large excess of sulphuric acid, and hence it does not prevent the formation of the Te42+ ion.

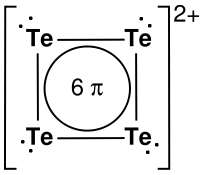

The deep red ion Te42+ has a very special structure, which was only unraveled recently.

Each tellurium atom has 6 electrons available in its outer shell. Four atoms are involved, so this would make up for 24 electrons to be distributed. However, the ion has a charge +2, so 22 electrons have to be distributed.

Eight electrons are involved in an ordinary σ-bond between tellurium atoms. These are represented by the lines between the Te-atoms. Another eight electrons are present as lone pairs on each of the Te-atoms, denoted by the two dots near each Te-atom. The 6 remaining electrons are delocalized in a resonance type of bond, which spreads over all four tellurium atoms (c.f. structure benzene). The entire structure has a charge +2. Geometrically, the ion is square planar.

![]() The

Te42+

is very water sensitive, and in water it immediately disproportionates as

follows:

The

Te42+

is very water sensitive, and in water it immediately disproportionates as

follows:

2Te42+ + 2H2O → 7Te + TeO2 + 4H+

![]() When

heating of the tellurium in the large excess of sulphuric acid is much stronger

(near boiling point of sulphuric acid), then the tellurium quickly is oxidized,

with production of quite some sulphur dioxide, which escapes as gas. A basic

tellurium(IV) sulfate is formed in this way, which appears as a white

crystalline solid:

When

heating of the tellurium in the large excess of sulphuric acid is much stronger

(near boiling point of sulphuric acid), then the tellurium quickly is oxidized,

with production of quite some sulphur dioxide, which escapes as gas. A basic

tellurium(IV) sulfate is formed in this way, which appears as a white

crystalline solid:

2Te + 5H2SO4 → SO3·2TeO2 + 4SO2 + 5H2O

The white solid SO3·2TeO2 is immediately hydrolyzed by water. It can be regarded as a basic sulfate. A discussion of this experiment on sciencemadness resulted in the mentioning of a possible structure:

mention of possible structure of the basic tellurium sulfate

Based on this, one can write [Te2O3]SO4 as a better formula of this compound.

When water is added to the liquid, with the white solid in it, it dissolves, giving colorless cationic tellurium(IV) species in solution, and sulfate ions. These cationic species are very prone to hydrolysis and when the pH is raised, they are converted to hydrous TeO2.

This behavior also nicely demonstrates, that TeO2 can act as a base. It is known that it also acts as acid, and hence, TeO2 is amphoteric. When TeO2 acts as acid, then H2TeO3 is formed, which splits off H+ ions. When it acts as base, then it absorbs H+ ions, but the precise nature of the resulting cationic species is not clear. For simplicity, the cationic species is written as TeO2·nH+(aq), but this certainly does not reflect its structure, it only emphasizes on the fact that TeO2 dissolves in strong acid, giving rise to cationic species.

The red/purple Te42+ ions also are oxidized further when the acid in which they are dissolved is heated more strongly. One way to express this reaction is as follows:

Te42+ + 9H2SO4 → 2[SO3·2TeO2] + 7SO2 + 8H2O + 2H+

The red/purple color disappears and only the white crystalline solid is left.

![]() Tellurium in its +4 oxidation state is easily reduced to elementary tellurium by

reducing agents. The hypophosphite ion reduces the tellurium(IV) back to

elemental tellurium, which appears as black precipitate.

Tellurium in its +4 oxidation state is easily reduced to elementary tellurium by

reducing agents. The hypophosphite ion reduces the tellurium(IV) back to

elemental tellurium, which appears as black precipitate.

![]() Tellurium in its +4 oxidation state is easily oxidized to tellurium in its +6

oxidation state. In the strongly acidic solution, orthotelluric acid is formed,

which can be written as TeO(OH)4. This is a weak acid, which

dissolves in water quite well and which is colorless in solution. The experiment

with the potassium dichromate demonstrates the oxidation of tellurium(IV) to

tellurium(VI). The orange dichromate is converted to green/blue chromium(III)

ions.

Tellurium in its +4 oxidation state is easily oxidized to tellurium in its +6

oxidation state. In the strongly acidic solution, orthotelluric acid is formed,

which can be written as TeO(OH)4. This is a weak acid, which

dissolves in water quite well and which is colorless in solution. The experiment

with the potassium dichromate demonstrates the oxidation of tellurium(IV) to

tellurium(VI). The orange dichromate is converted to green/blue chromium(III)

ions.

![]() Finally,

addition of sulfide almost certainly also leads to reduction of tellurium(IV) to

elemental tellurium, but apparently also other species are formed (sulfide of

tellurium?). This conclusion can be drawn, because the brown precipitate, formed

after adding sulfide does not dissolve as easily as the black precipitate,

formed after adding sodium hypophosphite. So, there definitely must be a

difference.

Finally,

addition of sulfide almost certainly also leads to reduction of tellurium(IV) to

elemental tellurium, but apparently also other species are formed (sulfide of

tellurium?). This conclusion can be drawn, because the brown precipitate, formed

after adding sulfide does not dissolve as easily as the black precipitate,

formed after adding sodium hypophosphite. So, there definitely must be a

difference.

![]()

![]() Selenium reacts with sulphuric acid

near its boiling point

as follows:

Selenium reacts with sulphuric acid

near its boiling point

as follows:

8Se + 3H2SO4 → Se82+ + SO2 + 2H2O + 2HSO4–

This reaction resembles the reaction with tellurium. Again, there is a mild oxidation, but now a positively charged ion is formed, consisting of 8 atoms.

Stronger heating does not result in further oxidation of the selenium. No SeO2-like species are formed in the concentrated sulphuric acid. So, here the analogue with tellurium stops.

![]() This Se82+ also is very water-sensitive

and immediately disproportionates, when added to water. This results in

formation of the red allotrope of selenium. The reaction equation is as follows:

This Se82+ also is very water-sensitive

and immediately disproportionates, when added to water. This results in

formation of the red allotrope of selenium. The reaction equation is as follows:

2Se82+ + 2H2O → 15Se + SeO2 + 4H+

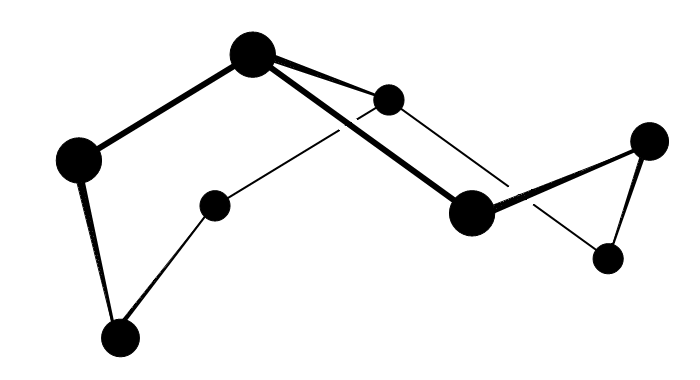

![]() The deep green Se82+ ion has a very

peculiar structure. The picture below shows the 3D-structure of the ion, where

the black balls are the selenium atoms, and the bonds are drawn as lines. The

total structure has a charge +2. The two 5-membered rings, which share one edge

(and hence two vertexes), have delocalized electrons in them. The shared edge is

a very long bond, its bond length is 284 pm.

The deep green Se82+ ion has a very

peculiar structure. The picture below shows the 3D-structure of the ion, where

the black balls are the selenium atoms, and the bonds are drawn as lines. The

total structure has a charge +2. The two 5-membered rings, which share one edge

(and hence two vertexes), have delocalized electrons in them. The shared edge is

a very long bond, its bond length is 284 pm.

![]()

With sulphur, the preparation of an ion of the form Sn2+ failed when concentrated sulphuric acid was used. With oleum, however, the reaction could be carried out easily. According to literature, Sn2+-ions exist, with n equal to 4 (yellow), n equal to 8 (deep blue), and n equal to 19 (deep red). With 20% oleum the S82+-ion is produced, the other ions apparently require other oxidizers or more extreme conditions.

The S82+-ion has the same structure as the Se82+-ion. The bond along the shared edge also has a very long distance between the sulphur atoms (283 pm).

Information about the cationic species of S, Se and Te is from the following book: Chemistry of the Elements, second edition by Greenwood and Earnshaw. Information about sulphur is on pages 664, 665. Information about Se and Te is on pages 759 and 760.